NXT has established a publishing house, Nybrogade Press, to channel and communicate hybrids of art, design, philosophy and calls to action traversing and inspired by Scandinavia. Initially we produce four high-quality monographs per year, touching on green design, arboreal politics, feminism and activist performance, as well as a multi-voiced volume of essays. The collection will be rich in surface and depth, distinctly designed and profoundly engaged in the all-consuming upheaval of the climate crisis. Two of our first publications have been read and reviewed by philosopher and vegetarian chef, Daniel Frank Christensen.

Marion Waller looking through her book at NXT

Book review – Natural Artefacts & The Clearing

By Daniel Frank Christensen

Reading Natural Artefacts and The Clearing both delivered as promised, inspiring new ideas about ecology and encouraging a greater sense of connection with other living things, as such even life itself. Both books communicate convincingly that, whilst a certain degree of destruction is an inescapable factor in sustaining life – not only human life – and as Todd reminds us referencing Latour: “we would do well to consider exactly what we depend on before making sweeping proposals for change on a planetary scale”. We can achieve much good and for more beings than merely ourselves by rethinking our position in the world, by acknowledging the interrelatedness of beings, and by acting accordingly as a part of, not master of, the totality of life on Earth.

…

In the early summer of this year, I had the pleasure of attending an event at NXT in Copenhagen, marking the founding of a new publishing house, Nybrogade Press, and launching two highly contemporary works. Both authors, French ecological philosopher Marion Waller, director of Paris’ Pavillon de l’Arsenal as well as former advisor to the Mayor of Paris – author of Natural Artefacts: Nature, Repair & Responsibility,– as well as the disarmingly engaging British architect, polymath and veritable tree hugger, Andrew Todd, who beyond writing The Clearing: How We Live and Die with Treesalso translated Waller’s title from French into English.

Waller and Todd held consecutive talks presenting their respective books, followed by a discussion with Peter Andreas Sattrup, head of green transition at Danish construction contractor NCC. Here, they reflected on the books, integrating many compelling first-hand insights on, for instance, Parisian urban planning in relation to selection of building materials and city heritage, environmental improvement policy, and the interrelatedness of production and destruction.

As the evening progressed I decided to get my newly purchased book by Marion embellished with a signature, and surprised me with a simple yet pervasively compelling prompt: “Dear Daniel, I hope this book will inspire you and give you new ideas about ecology.”

That is precisely what came of my readings.

Transcending oppositions

Natural Artefacts is a condensed and simplified work of scholarly philosophy and is structured a formal argument, yet it is formulated as a sequence of essays useful for a wider audienser invested in ecology. Waller’s writing is succinct, ordered and consistently, lucidly analytic, despite the philosopher’s metaphysical approach, Sorbonne education, and sharing thematic connections to thinkers like Bruno Latour and Donna Haraway, her writing style seems more comparable to, for instance, Peter Strawson or Willard Quine.

The book sets out to nuance current debates and positions within the entrenched conceptual dichotomy: nature vs. human. Waller challenges the integrity of this opposition by questioning how the terms are defined and used in practice: How is nature as an idea substantiated and differentiated from non-nature, or to use a string of antonyms such as artefacts, art, the artificial, technê, craft, and culture?

Extra-terrestrial detector

To elaborate, Waller asks how extra-terrestrials would be able to design a detection machine to identify and differentiate the existence and respective properties of artefacts and natural objects upon visiting Earth. Encoding a method based on an intuitively meaningful factor, regularity, Waller writes, would probably lead this alien device to label a bird’s wing as an artefact, whilst “it would classify bedsheets as natural objects”.

Looking at something like a bird’s nest following an origin approach would have the extra-terrestrials again reworking their device, inserting code to identify processes of spontaneity and planning, to enable telling the difference between this object and a human house. Although even at this stage of modification, the machine, beyond now also being geared to detect the aspects of form and function in construction processes, would most likely be confused about something like a woven basket, precisely because such “weaving is the result of forces both internal and external to it, in an ongoing interaction between human action and the raw material. Hence, Waller references a colleague’s proposed “paradigm inversion”: instead of “seeing every act of weaving as an act of doing, we must see every of act of doing as an act of weaving”, whereby perhaps all design, much like genetics, establishes the framework of a process and does not dictate in advance the final form.

Cutting to the bone, Waller argues, echoing Latour et al., that humans are inextricably part of nature, and like all species plant and animal, contribute to adding, shaping and depleting the qualities of our shared world. Therefore, as part of this world, humanity’s productions and presence does not necessarily preclude nature: It depends on whether or not our interactions leave space for ecosystem diversity and dexterity.

A new stewardship

Waller moves on to apply the concept of Natural Artefacts to questions of environmental stewardship, that humans can and do take regarding nature. In a concise critique of conservation and restoration, Waller argues that restoration approaches favoring ‘natural purity’ or untouched nature, not unlike essentialisms underpinning nostalgic nationalism, is a construct that chooses an ideal situation and composition of nature supposedly ‘right’ at some point in time. Rather, the goal should be to revitalise environments in terms of biodiversity and balance, thus aiming at “sustainability and resilience rather than the identical reproduction of past or present entities”.

As for the solution, Waller’s concrete proposal for ‘good natural restoration’ is, to recreate our dwellings in cities and beyond into forested gardens, transforming, in Waller’s words, baroque and “patrimonial” imperatives demanding conservation of “mineral cities”. In this regard Paris could become something more liveable and alive by interspersing avenues and rooftops, for instance, with biological layers to make “the world habitable for present and future living things by nurturing conditions for ecopoiesis”.

Ecopoiesis as a concept naturally lends itself to interpretation, and beyond the perhaps more commonplace meaning of the term denoting something like ‘terraformation’ or the ‘creation of conditions of self-sustaining life”, could also be read with a degree of poetic license from the Greek as ‘habitat creativity’ – as such perhaps an alternative ideal for economic productivity.

Well said, but we must cultivate our forests

In The Clearing, Andrew Todd as both an author and architect seems to operationalise ecological thinking in line with those of Waller. The essayistic nature of the book reads like a mixture of travelogue, cultural anthropology, literary critique, artisanal diary, political satire, family biography and grief journal. Similarly resonant with Natural Artefacts, speaking of wood, its fantastic qualities and products, Todd writes of his professional specialty and rhyming on the aforementioned impossibility of design: “As an architect I make wooden buildings in the full knowledge that they are partly alive and out of my control: I am a custodian and a composer of their energy and force. I set the scene, they act”.

Trees appear throughout the book in a great variety of roles of centrality to humankind, Todd writes, featuring prominently in origin myths from around the world and in venerated texts such as the epic of Gilgamesh, The Mahabharata and the iconic ten books of Vitruvius’ De architectura, not to mention the wood and fruit of Christian genesis fables such as those involving figs and their leaves so symbolic in announcing human self-awareness and, by extension, supposedly divinely delegated right of dominion of Earth.

Such perspectives are constantly interwoven in The Clearing with moving anecdotes about nurturing many forms of kinship, with Todd often weaving in arboreal puns, industrial histories and tongue-in cheek quips. The author shares recollections about caring for a bonsai tree, pruned, bound and transplanted as a part of and in itself an intergenerational undertaking, eventually a family member, beginning as a project with the author’s since-decreased father, himself a forester by trade.

Of place and people

One fabulous example of this takes place in Japan, which with its long mountainous spine forming 70 per cent of the nation’s land mass is naturally, or perhaps geographically, very well disposed toward forest conservation. Beyond such material constraint, Japan also has deep cultural traditions, Todd writes, demanding philosophical-spiritual respect for the woods:

“The balance and harmony of the Japanese landscape is held to belong to a tripartite collaboration between the passionate mountains (who capture water), the peaceful trees (who tame it) and the plain-dwelling humans who are able to use it in a steady flow from the hills to predictably husband the land”.

A Japanese term Todd mentions in reference to such culture, Satoyama, translated in the book as “the product of collaboration between people and place,” yet the author says that it is also vernacular for ‘plain’, which in the context of Japanese topography is precisely where a useable and arguably sustainable ‘clearing’ could be expected. Perhaps needless to point out, this concept seems strongly related to the forms of ‘good’ natural restoration practice we see with Waller’s project.

Everything on the table

A sense of grief, is present throughout The Clearing, wherein a sense of mournful appreciation is laid bare both concerning lost kin and the dire plight of our planet. Todd writes, for instance:

“For most of us, however, human life is not defined by cohabitation with trees, but destroying them and living in the voids we create. Human life takes place in the clearings, the clearings we have made with our axes and chainsaws. In much of our world our spiritual narratives, our economic and political systems and our general worldview are predicated on looking down on these wooden beings that – in reality – loom over us,”

Todd writes, like Waller, also sombrely referencing the idea of human exceptionalism that serves to justify our “grave incursions into the living matter which first welcomed us as naked, vulnerable bipeds.” I sense in Todd’s writing a similar hue of dark blue that I and many others know as climate grief, and in a sense, The Clearing reads as an advance obituary for planetary life as we know it. The book is, however, also a strong call to action and a caring reminder of what is at stake.

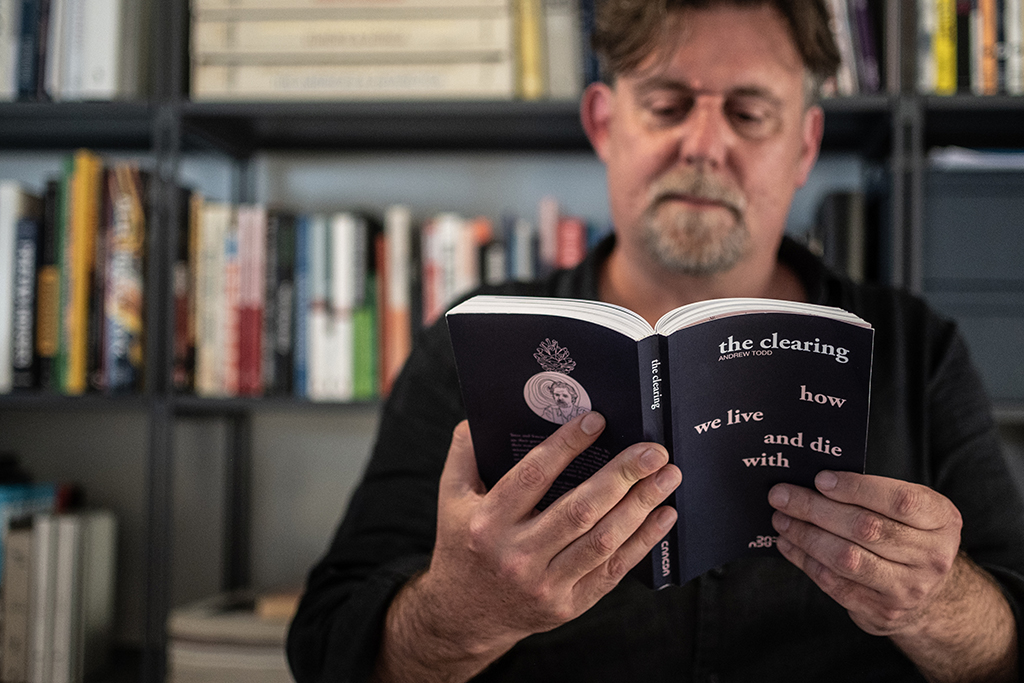

Andrew Todd looking through his book at NXT